Curator Danielle Thom talks about London's first and most fashionable music venues, the extraordinary Pleasure Gardens. Part of our series on the vanished world of night-life that thrived in Georgian and Victorian London.

The attractions of London’s pleasure gardens were many, from the glittering night-time illuminations to the sight of thousands of well-dressed visitors in fashionable silks, lace and jewellery. The principal entertainment on offer, at least officially, was music; and the performance of music shaped both the architecture and the experience of the gardens.

Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens season ticket, 1737-60

Depicting a singing siren with lyre.

At Vauxhall and at Ranelagh, eighteenth-century Londoners could hear the very best contemporary music from the most notable composers and performers of the day. The city was full of places to hear music, from the tavern fiddle to the Italian opera, but the pleasure gardens were notable because they promoted the latest in English music, and many well-known pieces received their debut there. Thomas Arne, who was Vauxhall’s musical director between 1745 and 1777, was responsible for the patriotic song Rule Britannia, as well as a version of God Save The King.

A Scottish visitor to London described his experience in 1739, showing how the performances shaped visitors’ experiences in the gardens. At the start of the evening ‘the music striking up, the whole company crowd from every part of the gardens toward the orchestra and organ; which gives a fair opportunity of meeting one’s acquaintance, and remarking what beaus, bells, and beauties are present.’

Later on, ‘the next piece is begun, the gardens being pretty full, the company crowd round the music and, by being forced to stand close, have an opportunity of taking a strict observation of every face near, and, as it frequently happens, of picking out companions for the remaining part of the evening.’ Finally, ‘towards the close of the entertainment some of the best pieces of music are performed with the utmost skill and care, in order to leave the stronger impression upon the audience of the elegance of the entertainment… When the music ceases for the evening, the chill of the night hurries the company to the water-side.’

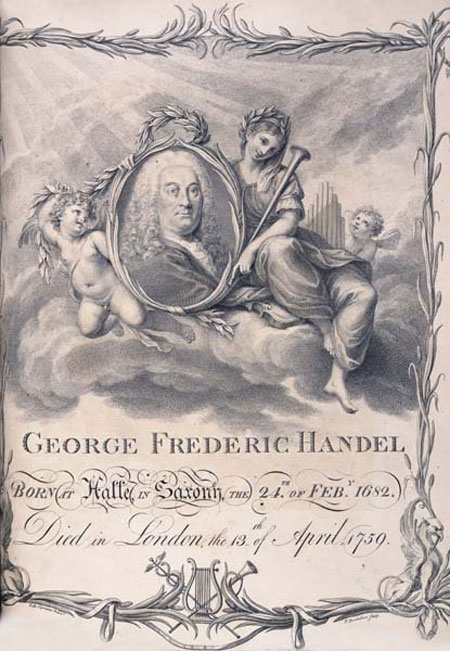

The composer best associated with Vauxhall Gardens was George Frideric Handel, who came to England as the Kapellmeister, or master of music, to King George I. Fashionable and well-connected, many of his pieces were performed in the gardens during the 1730s and 1740s, including the Vauxhall Hornpipe, written especially for the venue. When Handel’s Music for the Royal Fireworks was first rehearsed in the gardens, on the 21st of April 1749, 12,000 Londoners rushed to hear it. This reportedly caused a three hour traffic jam as carriages tried to cross London Bridge to get there; then the only bridge within the city. Events like this were the eighteenth-century equivalent of going to see Beyoncé perform at Wembley; and Handel was the star. So famous was the composer, and so closely linked to the gardens, that the proprietor Jonathan Tyers commissioned a statue of him. This was made by the leading sculptor Louis-François Roubiliac, and erected at Vauxhall in 1738.

Ranelagh also had its share of celebrity musicians. In 1764, the star of a charitable benefit concert was the eight-year-old Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who performed his own compositions on the harpsichord and piano. Londoners went into raptures at his youth and skill, and one newspaper described him as ‘the celebrated and astonishing Master Mozart, […] justly esteemed the most extraordinary Prodigy, and most amazing Genius, that has appeared in any Age.’ If Handel was an eighteenth-century rock star, seeing the young Mozart at Ranelagh might be the equivalent to being at an early Beatles gig.

Both gardens had dedicated buildings for musical performances. Ranelagh, which opened in 1741, was dominated by a vast rotunda, 120 feet wide and built in the fashionable rococo style. It had a concert space at its centre and private boxes, lounges and gaming rooms around the perimeter. Vauxhall, its older rival, originally had an octagonal orchestra stand, with the performers on a high platform so that all could see and hear them. Built in a classical style, it may have been the first structure in Britain purpose-built for musical performance. Not to be outdone by Ranelagh, Tyers built a rotunda in Vauxhall for wet-weather concerts, which opened in 1748.

A View of Vaux-Hall Gardens shewing the Grand Walk at the entrance of the Gardens, c.1756

Showing the music-building on the right.

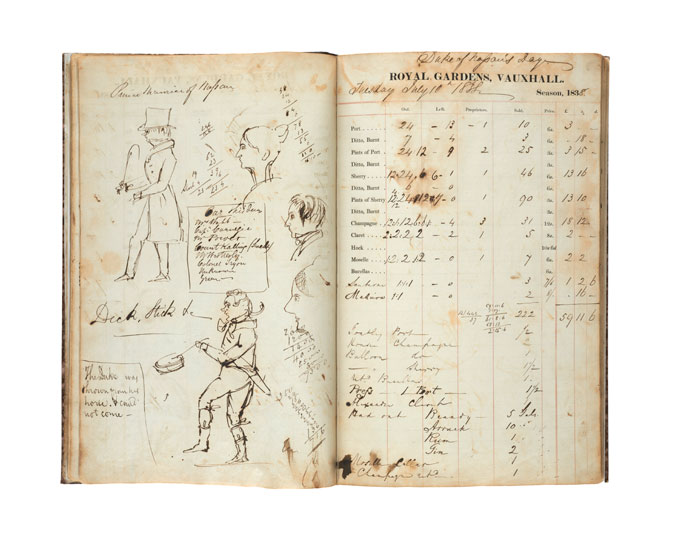

By the 1790s, the clientele of the pleasure gardens was changing, and so were their demands. When management of Vauxhall passed out of the Tyers’ direct control, the new proprietor introduced a variety of entertainments, such as hot air balloon demonstrations and – after 1816 - acrobatics. These were undoubtedly popular, but seen as downmarket novelties rather than high culture. The music changed accordingly, with precedence given to popular ballads and country dances. Vauxhall and its rival pleasure gardens were still places to hear music but, in the final decades of their existence, no longer the innovative venues they had once been.

Part of our series about London's Pleasure Gardens, the pinnacle of nightlife in 18th and 19th century London. Read more about the Pleasure Gardens: costume; music; masquerades; eating and drinking; toilets.

First published during #RedressingPleasure – thank you for helping us to crowdfund our new gallery of 18th century fashion!