Detecting cancer in human skeletons

Due to the fact that methods of detecting cancer in the past weren’t as reliable, it is very difficult for us to get an accurate picture of how common cancer was in the past from written records.

We can however, apply modern clinical imaging techniques such as radiography to human skeletal remains to record bone cancers in the past. Although the approach also has pros and cons, we can fairly compare the numbers of cases we see across different groups of skeletal assemblages using a consistent scientific methodology.

Wayne Hoban (Reveal Imaging, Ltd) undertaking radiographic imaging (Credit: J. Bekvalac)

The first type of cancer we looked for in the human skeletons was metastatic bone cancer. When a cancer has spread from another part of the body, it is said to have ‘metastasized’. Metastatic bone cancer is most likely to spread from a primary tumour in either the breast, prostate gland, kidneys, lung or thyroid gland. Metastatic bone cancer can either be ‘lytic’, creating a void in the bone, or it can be ‘blastic’, creating new extra bone growth.

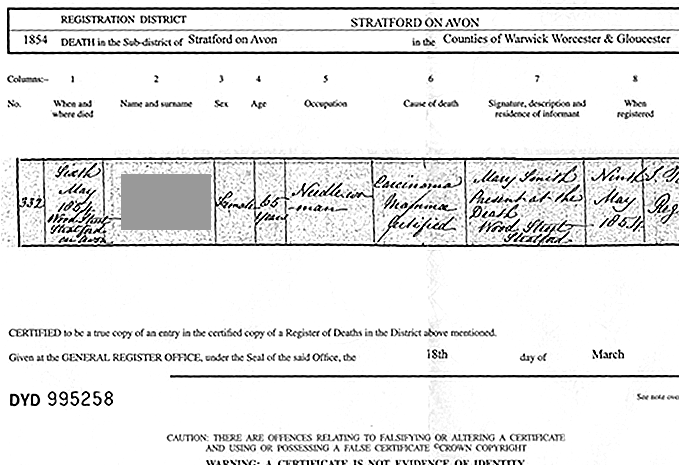

We found an example of this in one female individual in the skeletal assemblage from Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon. She could be identified from the presence of a coffin plate. Her death certificate stated that she had died at the age of 65 of ‘carcinoma mammae certified ’, or diagnosed breast cancer.

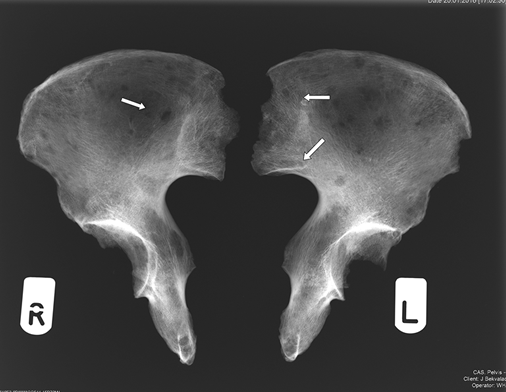

No observable (macroscopic) changes were present in the skeleton but using digital radiography, we did find a lesion in the left femur, indicated by a dark rounded area on the image of the bone, suggestive of a metastatic cancer lesion.

The second type of cancer we looked for was ‘multiple myeloma’. This is a cancer of the white blood cells or ‘plasma’. Damage caused to the DNA of the plasma cells causes them to produce abnormal cells that grow at an abnormally fast rate (proliferation). Over time, a series of further genetic mutations in the cells, some of which are caused by foreign substances, leads to the production of aggressive cancerous plasma cells. This leads to the typical multiple ‘raindrop’ lytic lesions in the bone, seen here as all the small dark rounded lesions in this radiograph of the pelvic (hip) bones.

Sternal ends of ribs (visceral surface) with image A showing multiple lytic (destructive) bone lesions (arrow) indicating multiple myeloma, middle adult male, Industrial London (FAO90 1879) and image B rib with no pathological changes, middle adult male, Industrial London (PGV10 2588) © Museum of London

In this example of multiple myeloma in the ribs, the small elongated holes in the bone can be seen quite easily by the naked eye, and it would not be necessary to take an x-ray. The rib below is normal and healthy in comparison.

We also used CT scans on some individuals to confirm that our observations based on the radiographs were accurate. While radiographs are 2D, CT scans consist of a series of 2D image slices that can be reconstructed into 3D models, providing a more accurate and better image of the bone.