Social status and obesity

In industrial London, high social status was a key risk factor in obesity.

In fact, high status females were three times more likely to be overweight or obese than low status females, and high status males four times more likely to be overweight or obese than low status males.

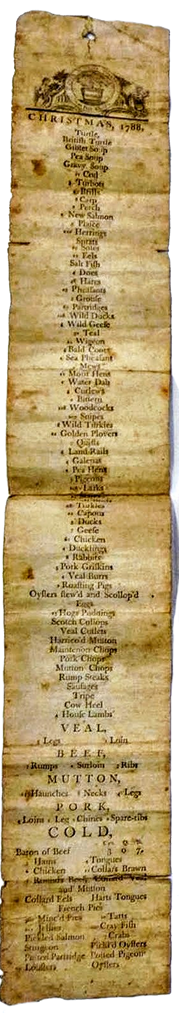

Bill of Fare

During the Industrial period, the traditional social hierarchy of Lord and Manor began to break-down, with a new ‘middle class’ emerging who had made their own wealth, exploiting the business opportunities that industrialisation brings. Emulating the aristocracy, the middle classes often held extravagant social events and banquets to display their wealth and social status, as well as to form new acquaintances and business contacts.

Consumerism and material wealth are central themes to industrialisation. New markets and exotic trading brought fresh opportunities to show off your social status by acquiring new and fashionable exotic goods. This included indulging in copious foodstuffs, which being newly discovered from abroad, were often very expensive.

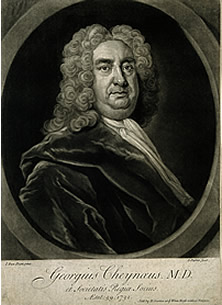

George Cheyne book cover

A first hand account of the excesses of London dining comes from George Cheyne (1672-1743), a physician practising in the city latterly known as ‘Dr. Diet’. Socialising with the ‘bottle companions, younger gentry and free-livers’, Cheyne describes himself as growing ‘daily in bulk...excessively fat, short-breathed, lethargic and listless’. After growing to 32 stone in weight and suffering bad health as a consequence, he moved to the countryside, changed to a lacto-vegetarian diet and lost the pounds.

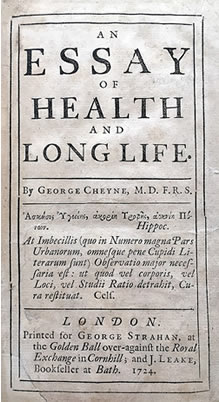

George Cheyne's Essay of Health & Long Life

To treat obesity, Cheyne promoted this first ‘fad’ diet along with rigorous exercise regimes in his book ‘An Essay of Health and Long Life’, which was so popular it was reprinted four times in its first year. Dieting and restraint subsequently became a fashionable behaviour for the upper classes.

The popular new foodstuff that was contributing to obesity in the Industrial period was sugar. The demand for sugar spread like wild fire and initially, it was a high status food stuff that only the wealthy could afford it. It was often taken with tea, also very popular amongst the wealthy.

Sugar later became much associated with female dining out and in the late 18th century, confectioners and tea gardens offered sophisticated venues for ladies of social standing to socialise and consume the latest sweet treats such as pastries, sugar plums, jellies and bonbons.

Demand for sugar grew and grew. By 1800, consumption of sugar in Britain is estimated to have risen by 2500% over 150 years and at the centre of this trade was London. It’s production and supply became cheaper and cheaper to consumers, allowing it to become an easily obtained, daily commodity; but at what cost?