Defining old age in the industrial period

The physical capacity of our bodies to work was also an important factor in the industrial period.

Karen Chase in her research into age found evidence that glassworkers might expect to retire at 40, carpenters at 50 and engineers at 55. There was still no official age of retirement or state pension, so often private pensions were paid into that were administered by ‘Friendly Societies’. During the mid to late 19th century, these societies often stated that pensions could be drawn from the age of 50.

Friendly Society Marching Banner (Reverse) for the Order of Foresters (East Lothian Museums CC by NC-SA 2.0)

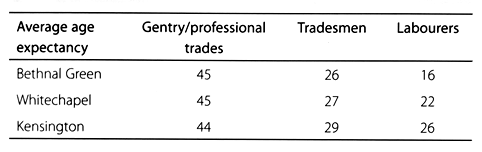

This decrease in the age at which one’s physical capacity to work was expected to diminish may be related to the much more intensive and hazardous nature of industrialised work. Edwin Chadwick carried out a survey of life expectancy, looking at factors like occupation, social status and poverty, which culminated in his Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain, published in 1842. This subsequently lead to major public health reforms.

He concluded that those living in the countryside lived longer than those living in the towns. He also found that that occupations in the City had a shocking impact on life expectancy. On average, males of a professional trade had an average life expectancy of 43 years, almost double that of a labourer, who had a life expectancy of just 22 years. This occurred irrespective of the borough an individual lived in.

Experiences of age and ageing were therefore different according to your occupation and where you lived. The challenge for this project was to see if we could identify the effects of ageing in the human skeleton and how this changed over time in different groups.

Osteoarthritis of the hip joint in an older male, Industrial London (OCU00 681) shiny bone surface, eburnation (red arrow) © Museum of London

One of the most common degenerative diseases we associate with old age today is osteoarthritis. It causes degeneration of the joint leading to irregular bone outgrowths around the joint, as well as porosity and eburnation (polishing) of the joint surface. Osteoarthritis most frequently affects the knee joint (most commonly in women) followed by the hip (most commonly in men). Occupations involving kneeling and squatting are associated with osteoarthritis of the knee, whereas heavy lifting and load bearing are linked to osteoarthritis of the hip.

Looking at osteoarthritis in these joints, we found that rates of osteoarthritis were much higher in the rural towns and villages outside of London in both the pre-Industrial and Industrial periods. This is likely to be due to the labour intensive nature of the agricultural industry, which played a prominent role in the local economies of rural settlements. This intensified during the Industrial period with the Second Agricultural Revolution from 1700, when agriculture intensified and there was an increase in the labour force. The skeletal evidence tells us that this level of manual labour appears to have prematurely aged the body and that this was more common in people living in rural environments.

We also found evidence of other influences on the ageing process in the past that are quite different from what we experience today.