Industrial old age care

Between 1851 and 1911, 86-93% of men aged 60 and over were still working to support themselves financially, with some perhaps drawing on small private pensions provided by Friendly Societies.

However, for those unable to work at all and that were in financial hardship without support, things became very bleak during the Industrial Period.

The Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 was designed to remove those people out of work from the streets and this very often included the elderly who could no longer work due to frailty or injury. Attempts to banish the elderly poor to the workhouse included the use of terms such as ‘old age’, ‘lunacy’ and ‘imbecility’ that were often obscured and interchangeable, according to Karen Chase’s analysis of workhouse records.

The notion of restricting the movement of parishioners actually originated in the Statute of Cambridge 1388. This Statute was created to restrict the movements of labourers out of the parish during the economic crisis caused by the Black Death pandemic. By restricting people's movements, they ultimately became wards of the State. The State rather than the Church then became financially responsible for the poor.

By the Tudor period, reforms had been made via the Act of Relief for the Poor 1601 to distinguish between those who were genuinely unemployed and those who could but were falsely claiming poor relief. The latter were to be dealt with by making them work in a ‘house of correction’, while the old and infirm could claim outdoor relief.

An economic crisis in the 1830’s meant that this system was no longer sustainable and new reforms meant that poor relief could only be obtained if an individual entered a workhouse. Workhouses were conceived of as a deterrent to prevent reliance on the State for money. The previous punitive ethos of correcting the ‘idler’ was embedded in the draconian measures employed in these new workhouses. Inmates were expected to work to pay for their keep, often up to 11 hours a day. Males and females were segregated. It was no sort of retirement at all.

Even worse, if you died a pauper in a workhouse and no-one claimed your body or paid for your burial, after the Anatomy Act 1832, your body would be sold to medical practitioners or universities to be anatomically dissected. With some workhouses being run to make a profit, the elderly poor had become not only a exploited source of free labour but an entirely disposable asset.

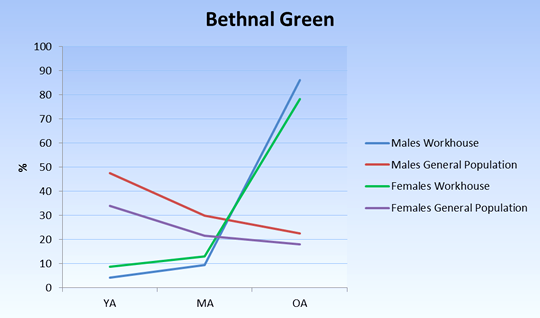

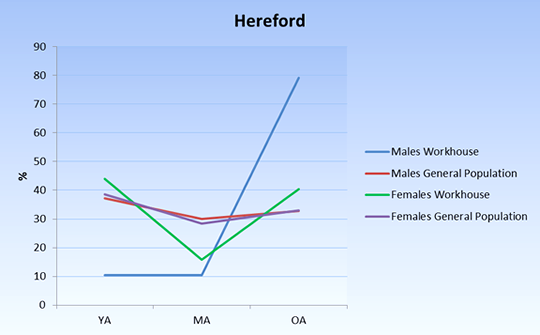

Our analysis of workhouse records shows that 70-80% of the adults in workhouses were over the age of 50. The vulnerability of elderly males was particularly apparent. Outside of London, numbers of old age male inmates were much higher than females because older females were more likely to be incorporated into extended families as care givers.

Age profile demographics comparing workhouse and general population from 1881 census data for Bethnal Green (www.workhouses.org.uk ) (YA = Young Adult, MA = Middle Adult and OA = Old Adult

In London, however, old age males and females were equally represented in workhouses. Migration into the city seems to have broken familial links, with the result that neither low status elderly males nor females had much family support in their old age.

Age profile demographics comparing workhouse and general population from 1881 census data for Hereford (www.workhouses.org.uk ) (YA = Young Adult, MA = Middle Adult and OA = Old Adult

Next: Provision of care today