Interpersonal violence

The dark side of the city, and indeed of many towns and villages, is revealed in numerous historical documents testifying to tragic or somewhat sinister human misdemeanours.

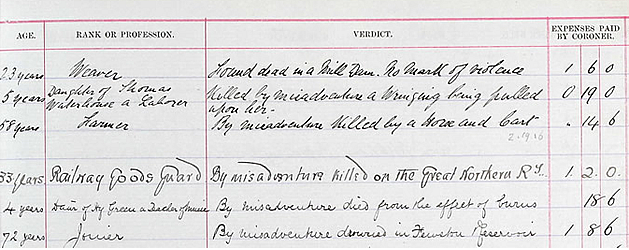

While we are generally unable to directly interpret fractures in the skeleton as resulting from personal malicious intentions, Coroners records and death certificates provide evidence of some of the more grisly aspects of human behaviour.

One of the most common fractures that we can see that may result from interpersonal violence are broken noses (nasal fractures) and boxer’s fractures (fractures to the 5th metacarpal in the fist). Both these fractures occur most commonly from fighting but can also result from a fall, so their presence is open to interpretation. It is also unclear as to whether such fractures might have been caused by sporting injuries or unlawful violence. Nonetheless, nasal fractures occur most commonly in males, the majority of those being low status, from areas such as the East End of London. This is a trend that is seen today and is often associated with drunken brawls.

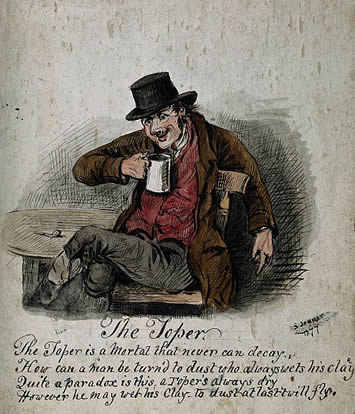

The Toper, or hardened drunkard, S. Jenner, 1877 (Wellcome images)

In the Victorian period, Henry Mayhew observed institutionalised alcohol consumption among lower class males who, prior to an Act of Parliament in 1848, would compete against each other, bartering with gangmaster publicans to secure their day’s work at the docks. Wages were also paid by the publicans in the pub and included payments in porter or rum. Mayhew identified the institutionalised alcohol consumption to the frequently seen violent behaviour, which included domestic violence against women.

A similar pattern was seen outside of London, with rates of violent deaths being much higher in the densely populated North Shields (7.1%), a town also economically dependent on its port, compared to more rural market towns like Stratford-upon-Avon (2.2%). Seemingly, the connection between alcohol and violence was strengthened by urban living among working class males.

Based on death certificates, the General Registrar’s records include collated data on violent deaths. 5.9% of all deaths in young adults and 5.2% of all deaths in middle aged adults were attributed to violence. This was almost double that of the rate in old aged adults.

Hotspots of higher rates of violent deaths in the City were recorded in the poorer and more densely populated areas of London. High status Chelsea had the lowest rate of violent death whereas low status Spitalfields had the highest. It is interesting to see that pre-industrial Bow had quite low rates of skeletal evidence for interpersonal violence while it was still a small rurally located settlement, yet after the area became urbanised and densely populated during industrialisation, rates of violent deaths were high.

Next: Traffic