Diabetes

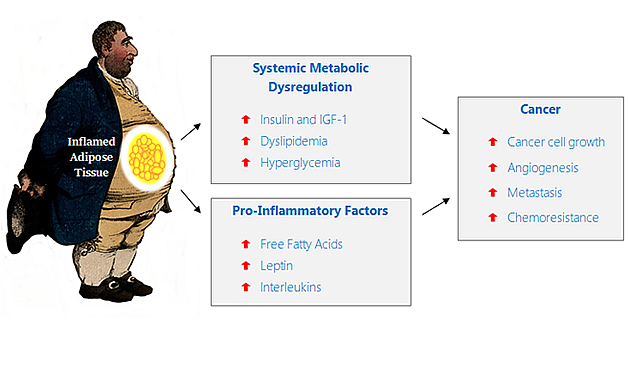

In addition to causing inflammatory dysregulation, an excess of fat also breaks our metabolic system, causing the dysregulation of insulin. Insulin controls how glucose is absorbed and processed.

When we are overweight or obese, the body will prioritise the use of the free fatty acids from body fat for energy rather than use glucose. This causes a problem because cells using the free fatty acids as a source of energy become densensitized to insulin (insulin resistant) and do not take up glucose properly. The levels of glucose then increase in our blood.

Unfortunately, to try and deal with the increased glucose levels and to reduce them, the pancreas generates more insulin, eventually causing diabetes. Fat accumulating in the liver plays a particularly important role in the maintenance of insulin, and as such visceral fat is a greater predictor of diabetes compared to overall body weight.

High insulin levels also increase the levels of growth factors (such as insulin-like growth factor IGF-1) available to cells. The more growth factor available, the more they replicate, leading to their proliferation, encouraging cancer development.

Hormones

Hormones are messengers that interact with each other as well as other biochemical compounds in the body to help regulate metabolism. They are secreted by the endocrine system. Leptin (secreted by fat cells to control appetite), insulin, oestrogen and androgen are all hormones that are key to the production and distribution of fat around the body. If we are obese, we are more prone to accumulating even more body fat because of the associated hormone levels.

As well as causing glucose problems, insulin dysregulation also leads to increase of androgens (male hormones) and the co-occurring obesity simultaneously results in a reduction of the sex-hormone binding globulin (SHBG). This protein binds to the sex hormones oestrogen and testosterone, protecting our bodies from excessive quantities of them. Left unbound, these hormones become bio-available, having negative impacts on our health.

In women, abdominal fat is a major source of oestrogen and androgen after the menopause; excessive fat therefore increases levels of bio-available oestrogen and androgen by acting to reduce levels of SHBG and increase sex hormone production. Excess oestrogen made by fat cells is a problem to our bodies because it promotes the proliferation of mammary epithelial cells and intestinal stem cells, which are involved in cancer. There is a direct relationship between obesity, high oestrogen levels and breast cancer in both women and men.

Current health statistics based on medical data show record levels of obesity in the UK. But is this really a recent trend? Did industrialisation impact on our body size and can we use human skeletal remains to detect this? And did people think these changes to body shape were good or bad?